Call Me Maybe?

What I learned solving the fly.io distributed systems challenges.

The title of this post is inspired by kyle kingsbury’ series of articles like this one and this one and of course:

1. Echo

saying hello world! but distributed systems style, it’s mostly boilerplate setup, reading the maelstrom docs and the go client docs, we instantiate a maelstrom node/binary, define an RPC style handler and return messages:

func main() {

n := maelstrom.NewNode()

// Register a handler for the "echo" message that responds with an "echo_ok".

n.Handle("echo", func(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

// Unmarshal the message body as an loosely-typed map.

var body map[string]any

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// Update the message type.

body["type"] = "echo_ok"

// Echo the original message back with the updated message type.

return n.Reply(msg, body)

})

// Execute the node's message loop. This will run until STDIN is closed.

if err := n.Run(); err != nil {

log.Printf("ERROR: %s", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

}

2. Unique ID Generation

In a single node/computer, generation of unique ids is typically achieved using a growing monontonic sequence such as a counter or the system clock.

In the view of a distributed system where each node could increment this counter simultaneously and the system clock is unreliable there needs to be some way of solving this global clock synchronisation problem of not only skewing different “times” but logical ordering of events. What to do? We also want to prevent the need to exchange messages or co-ordination so lamport clocks are out!

- A pseudo logical event clock where we can represent causal dependencies as combinations of properties of our system for e.g the system clock + orignating node id + a random request id(tie breaker). Luckily for this challenge there aren’t requirements for space or ordering or causality, only global uniqueness, which is naive but isn’t too far off more sophisticated schemes 1 2 3

func genNaive(nodeID string) int64 {

requestID := strconv.FormatInt(rand.Int63n(100), 10)

sequenceId := strconv.FormatInt(time.Now().UnixMicro(), 10)

originId := nodeID[1:]

identity := originId + requestID + sequenceId

if id, err := strconv.ParseInt(identity, 10, 64); err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

return 0

} else {

return id

}

}

hash a seed over a really large key space (2**128 - 1) - a uuid.

The use of a central authority, such as an atomic clock + GPS and/or other clever distributed algorithms4 provided by a time server(s).

3. Broadcast

Our first “official” distributed algorithm! a way to gossip information to nodes. Incrementally we scaffold basic messaging, sending data efficiently, simulating network partitions, variable latencies and interesting node topologies!

We keep all data we’ve seen in-memory in a simple “store”:

type store struct {

index map[float64]bool

log []float64

sync.RWMutex

}

// a session is a wrapper instance of a maelstrom node

// that can read/write from a single store and `handle` messages

type session struct {

node *maelstrom.Node

store *store

retries chan retry

}

reading, we simply take a read lock, respond with what’s in our log so far.

If we get a broadcast message we concurrently attempt to send it to all our neighbours, excluding ourself, store it in log and index so we can test if we’ve seen this message before and short circuit duplicate broadcast replies:

// spam everyone in this network we know of, and so on...

for _, dest := range n.NodeIDs() {

if dest == n.ID() {

continue

}

wg.Add(1)

go func(dest string) {

deadline := time.Now().Add(400*time.Millisecond)

bgd := context.Background()

ctx, cancel := context.WithDeadline(bgd, deadline)

defer cancel()

defer wg.Done()

_, err := n.SyncRPC(ctx, dest, body)

if err == nil {

return

} else {

// failure detection up next!

}

}(dest)

}

wg.Wait()

Our failure detection algorithm is a simple FIFO queue using go’s channels, for the un-initiated in go-ism, it’s conceptually an “atomic circular buffer”, if that doesn’t mean much – it’s a ‘concurrent safe queue’, so we can handle network partitions and variable latency async! We send messages into a buffered channel, in our else block and read it (if/when) we have to retry in a seperate goroutine(s):

s.retries <- Retry{body: body, dest: dest, attempt: 20, err: err}

we guess-timate a queue size (I’m not 100% about this bit lmk if I’m wrong!):

/*

little's law: L (num units) = arrival rate * wait time

rate == 100 msgs/sec assuming efficient workload,

latency/wait mininum = 100ms, 400ms average

100 * 0.4 = 40 msgs per request * 25 - 1(self) nodes

= 960 queue size, will use ~1000

*/

var retries = make(chan retry, 1000)

The spurious errors and on/off successes and failures making this were… interesting to debug! non-deterministic systems are… something.

Anyway, a few failureDetector go routines are spawned and sleep until messages are in the queue.

for i := 0; i < runtime.NumCPU(); i++ {

go failureDetector(s)

}

What suprised me was the tweaking of the deadline a longer deadline would lead to consistently more reliable delivery vs retrying in smaller intervals – this should have been obvious, but I only understood this in hindsight.

there’s always a trade-off between wrongly suspecting alive processes as dead (producing false-positives), and delaying marking an unresponsive process as dead, giving it the benefit of doubt and expecting it to respond eventually (producing false-negatives).

Which is to say a shorter deadline can make a more efficient algorithm with lower latency, but it’s less accurate and detects down nodes less reliably leading to more retry storms and eventually possibly overwhelming the partial async timing model assumptions.

// a naive failure detector :)

func failureDetector(s *session) {

var atttempts sync.WaitGroup

for r := range s.retries {

r := r

atttempts.Add(1)

go func(retry retry, attempts *sync.WaitGroup) {

deadline := time.Now().Add(800 * time.Millisecond)

ctx, cancel := context.WithDeadline(context.Background(), deadline)

defer cancel()

defer attempts.Done()

retry.attempt--

if retry.attempt >= 0 {

_, err := s.node.SyncRPC(ctx, retry.dest, retry.body)

if err == nil {

return

}

s.retries <- retry

} else {

log.SetOutput(os.Stderr)

log.Printf("dead letter message slip loss beyond tolerance %v", retry)

}

}(r, &atttempts)

}

atttempts.Wait()

}

A perfect timeout-based failure detector exists only in a synchronous crash-stop system with reliable links; in a partially synchronous system, a perfect failure detector does not exist

– https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/teaching/2122/ConcDisSys/dist-sys-notes.pdf

and finally we optimise! we’re sending far too many messages and flooding the entire network! even if it’s impossible to be both accurate and fast, we try anyway – gotta get those p99s up! there’s a hint about network topology so let’s re-examine that:

var neighbors []any

func (s *session) topologyHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

var body = make(map[string]any)

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

self := s.node.ID()

topology := body["topology"].(map[string]any)

neighbors = topology[self].([]any)

return s.node.Reply(msg, map[string]any{"type": "topology_ok"})

}

For this bit, I had to draw up the messsaging flow of the network topology on pen and paper. First I tried to send only to immediately connected neighbours. For example in a 5 node cluster of a, b, c, d, e a would neighbour b, c and so on forming a grid:

This is O(n) * sqrt(n):

a ++ b ++ d

+ + +

c ++ e /

instead of a spamming b, c, d and e and so on which is O(n)^2

-- // spam everyone in this network we know of, and so on...

-- for _, dest := range n.NodeIDs()

++ // send to our "overlay" neighbors only

++ for _, dest := range neighbors

Database Internals chapter 12 and the maelstrom docs were also super helpful on where to go about exploring options, network topologies for broadcast are a deep topic, so we’ll only review a very tiny subset we’re interested in:

- a fully connected grid mesh (what we had before) to quote wikipedia:

Networks designed with this topology are usually very expensive to set up, but provide a high degree of reliability due to the multiple paths for data that are provided by the large number of redundant links between nodes

- a tree topology - let’s revisit spanning trees. We’re presented with seemingly contradictory goals - fast low-latency and reliable accurate broadcast, in a 25-node cluster with partitioned networks. What to do?

Let’s say each node in a 6 node cluster forms a grid, each possible route from a node to a node:

a ++ b ++ c

+ + +

d ++ e ++ f

We can construct a “temporary overlay” over sub portions of this mesh, which is essentially a small tree from the point of view any node say a to its reachable neighbours:

b---/e

/ \f

a /

\ /d

\c

\

This tree is weighted by the cost it takes to reach each neighbour and a minimum spanning tree represents the “cheapest way there”, well now that’s one way of efficiently routing messages quickly, latency goes down, but… our overall protocol is now more brittle. If an “important” link between small sub-trees is broken the overall protocol is less reliable. Are there hybrid options?

To keep the number of messages low, while allowing quick recovery in case of a connectivity loss, we can mix both approaches — fixed topologies and tree-based broadcast — when the system is in a stable state, and fall back to gossip for failover and system recovery

I briefly discovered but did not implement other interesting hybrid algorithms/protocols 5 6 7 such as PlumTrees(the search term is “epidemic Broadcast Trees”), SWIM used by Consul’s serf, HyParView & HashGraph, and of course fly.io’s corrosion (built specifically for service discovery) or consul’s memberlist8 and more!

NB: My final solution isn’t as efficient as it could be:

It’s above the minimum target for “chattiness” ie 30 vs 30.05824 msgs-per-op with --topology tree3 which is a - [b, c, d]:

:net {:all {:send-count 55144,

:recv-count 55144,

:msg-count 55144,

:msgs-per-op 32.11648},

:clients {:send-count 3534, :recv-count 3534, :msg-count 3534},

:servers {:send-count 51610,

:recv-count 51610,

:msg-count 51610,

:msgs-per-op 30.05824},

:valid? true},

but on target for latency:

:stable-latencies {0 0,

0.5 148,

0.95 354,

0.99 420,

1 457},

This makes sense, we could shave off even more redundant ack messages by using async n.Send which doesn’t expect a response/ack, but it makes it more difficult to be able to have timeouts or detect failure reliably a good middle ground is some kind of periodic polling mechanism with a time.Sleep empirically eyeballing what might be a good fit or a more sophisticated probabilistic model like Phi-Accural.

I think it’s good enough as I’ve better intuited the trade off here. Maelstrom has a “line”, “grid” and several spanning tree topologies by using one kind of network for example across the “line”:

a ++ b ++ c ++ d ++ e ++ f

or “ring” like riak5, you loop back around and can pass even fewer messages/duplicates but risk greater latency.

4. Grow-Only Counter

Next up is strong eventual consistency with Conflict Free Replicated Data Types! 9 These allow us to replicate some data say a count of an integer i32 across nodes by being available and partition tolerant guaranteeing that at some unknown point in the future, it converges to the same state for every participant, given certain properties are pure, in the functional programming sense ie – lack side effects like say “addition” of integers and the order in which this operation(s) is carried out doesn’t affect the total result, also known as – commutativity:

+1

(node a) (node b) (node C)

an increment on a is replicated to b and c eventually as:

a few moments later...

+1 +1 +1

(node a) (node b) (node C)

and can as well happen as:

+2 +1

(node a) (node b) (node C)

we guarantee somehow, regardless of each addition operation occurs at some time T_1, even if another addition occurs concurrently at T_2,

because it’s commutative , there’s no contradiction that affects the final result when the network partition eventually heals, nor is co-ordination necessary.

eventually consistent ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

+2 +2 +2

(node a) (node b) (node C)

Total count = 6

We’re given a sequentially consistent key-value store service and can use this to keep track of the current count on each node, each increment is called a delta, this greatly simplifies the problem:

deadline := time.Now().Add(400*time.Millisecond)

delta := int(body["delta"].(float64))

ctx, cancel := context.WithDeadline(context.Background(), deadline)

defer cancel()

previous, err := s.kv.Read(ctx, fmt.Sprint("counter-", s.node.ID()))

if err != nil {

result = delta

} else {

result = previous.(int) + delta

}

err = s.kv.CompareAndSwap(ctx, fmt.Sprint("counter-", s.node.ID()), previous, result, true)

and to return the current total count:

for _, n := range s.node.NodeIDs() {

count, _ := s.kv.ReadInt(ctx, fmt.Sprint("counter-", n))

result = result + count

}

However, say that we don’t have a magical SeqCst store somewhere to pull out of our pocket for co-ordination of state, there are two approaches in theory:

- operation transform

- state transform

Roughly, sharing only the “delta” or current update ie add 1 to the current global count is indicative of an operation-based design contrasted with sharing the entire the count state a state-based design10, for an integer this difference might seem trivial but it has deeper implications for more complex data structures, one of the big seeming disadvantages of an operation based representation is it requires a reliable broadcast with idempotence/de-duplication, retry ordering and “reasonable” time delivery semantics, which means if you’re unlucky… state could diverge permanently, while the state based representation can tolerate partitions slightly more gracefully but requires more data over the wire which monotonically increases, which later gets “merged” and makes deletion more complex.

In summary, as long you can guarantee certain properties(associativity, commutativity, idempotence) it’s possibly to resolve conflicts between replicas given certain constraints. All we need is an extra “replicate” handler which leverages the previous broadcast from before to propagate the delta ‘operationally’ which often converges correctly but sometimes doesn’t? maybe I’m doing it wrong idk.

func (s *session) replicateHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

var body map[string]any

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

delta := int(body["delta"].(float64))

localCount += delta

return s.node.Reply(msg, map[string]any{"type": "replicate_ok"})

}

Other varieties exist like PN Counters which support subtraction/decrements, the G-Set – a set and much richer primitives which includes tree models that mirror the DOM and sharing JSON! but that’s enough for now. Libraries that abstract this away and allow you build super cool collaborative multiplayer stuff like google docs and figma are: YJS or automerge and elixir/phoenix’s very own Presence on the server side which implements the Phoenix.Tracker integrated with websockets and async processes so you can just build stuff, much wow! Ever wondered how discord’s “online” feature works? it’s CRDTs all the way down, you can trivially experiment with implementing this in phoenix!

5. Kafka-Style Log

As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect.

It’s a bird, it’s a plane… it’s tiny kafka! No, not that kafka. This one’s what people use as a message bus, or broker, or messsage queue or event stream, event sourcing all the words, as it turns out stream processing is a big deal and super important infra11

Apache Kafka is an open-source distributed event streaming platform used by thousands of companies for high-performance data pipelines, streaming analytics, data integration, and mission-critical applications.

In a nutshell this is a multi-producer, multi-consumer problem, a classic computer science/OS concurency problem aka the “bounded buffer” problem, with a twist.

You have ‘producer’ or writer threads, and ‘consumer’ threads which process or transform the written data, how to connect the two? – a shared buffer or ‘channel’ that both threads can access and synchronize r/w access to.

go’s channel abstraction solves a subset of this generalised problem, yet, here as hinted we have key differences in assumptions:

- when you read from a channel, this “event” is dequeued or destroyed.

- It’s guaranteed this destructive r/w will happen or it won’t, exactly once.

- There’s effectively a reliable link between the producing go routine and the consuming go routine, it’s just a pointer hop away.

- goroutines may panic or fail and be observed to do so immediately, transparently and consistently according to the runtime memory model

- Everything happens in main-memory

Each of these assumptions can be sent to dev/null:

- the network is unreliable

- failure is everywhere

- latency might as well be failure

- concurrency is weird - duplicates, re-appearing, disappearing.

- time is a lie

Except the first, this “event” is dequeued or destroyed:

In the classic publisher/subscriber model of protocols like AMQP, a publisher “pushes” messages over the wire via a router known as an exchange to the broker which has an index queue and persistent/on-disk store queue (durably or transiently) which in turn actively fowards the message to the consumer until it ACKs this message then it is typically destroyed/removed 12.

The persistent data structure used in messaging systems are often a per-consumer queue with an associated BTree or other general-purpose random access data structures to maintain metadata about messages.

Producer | | broker --> | consumer

Producer -> 'push' | <- exchange -> | queue --> | consumer

Producer to exchange | | queue --> | consumer

However Kafka is a log based message broker not a queue.

What’s the difference?

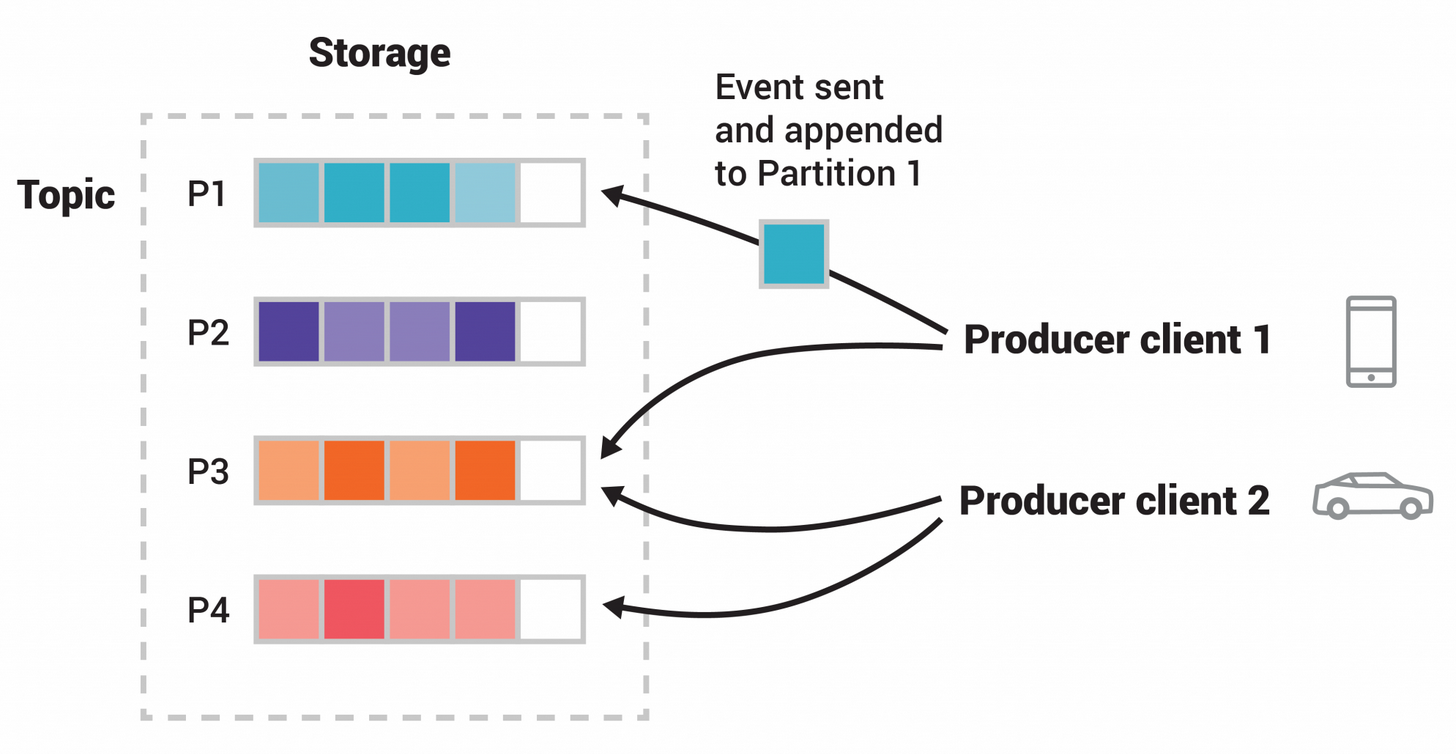

This nice diagram from the docs gives an overview at a high level:

In between producers and consumers is a broker, inside said “broker” server, we have the concept of “topics” basically a set of bounded buffers and partitions in the image: (P1, P2, P3, P4) – in the spirit of divide and conquer we split up the big problem into little one’s, so we can process those individually – horizontally, in parallel.

Producer -> | | <- consumer

Producer -> 'push' | 'topics' are partitioned | 'pull' consumer(s)

Producer -> to topic | via some mechanism | <- consumer

However there’s a big problem – this is a distributed system, how do these “bounded buffers” share the same view?

we need to ensure that every replica of the log eventually contains the same entries in the same order even when some servers fail 13

We’re interested in one neat thing – it provides a durable replicated log14 15 16. There’s a common aphorism in database rhetoric, “the log is the database” - is that true? idk but replicated logs are very useful in distributed systems and databases.17

At its heart a Kafka partition is a replicated log. The replicated log is one of the most basic primitives in distributed data systems, and there are many approaches for implementing one.

The log is a totally ordered, immutable grow only sequence of “events” 18, sound familiar? this suspiciously sounds like a WAL – and infact it is! Kafka even has transactions??! but more on that later.

Kafka organizes messages as a partitioned write-ahead commit log on persistent storage and provides a pull-based messaging abstraction to allow both real-time subscribers such as online services and offline subscribers such as Hadoop and data warehouse to read these messages at arbitrary pace. 13

Hopefully this explains why a replicated log13 17, partitions need to have a consistently ordered view, yet how exactly does a log give us these properties? some observations:

- a position/offset is a “timestamp” independent of a system clock

- reading state from this position is a deterministic process

- write is simply an atomic

append, to a cell that is “filled” or “not”. - an offset is monotonically increasing – fun with binary search!

(so many synonmyns!)

entry/tuple/event/message: {key, value, offset}

[{k1, hi, 0}, {k2, hello, 1}, {k2, world, 2}, {k1, foo, 3}, {k3, baz, 4}}]

Notice that keys can appear more than once and the latest entry for a key is its “current” value, each offset denotes a version of this event.

To replicate this log, two general approaches are considered 13 19:

- primary-backup replication

- and quorum-based replication

In a primary-backup setup, we elect and maintain a leader which is responsible for the total order and strong consistency:

A primary therefore assigns continuous and monotonically increasing serial numbers to updates and instructs all secondaries to process requests continuously in this order.

Kafka has historically shippped quorums via a zookeeper/ZAB layer, but has recently provided raft as an alternative. Note how the abstractions are layered:

We rely on the quorum-based Apache Zookeeper service for making consensus decisions such as leader election and storing critical partition metadata such as replica lists, while using a primary-backup approach for replicating logs from leader to followers. The log format is much simpler with such separation since it does not need to maintain any leader election related information, and the replication factor for the log is decoupled from the number of parties required for the quorum to proceed

Which apparently raises interesting questions for operability, durability and delivery semantics folks seem to have strong debates and opinions on. There’s a common association between the WAL and durability, but this is not necessarily true. In this context, the WAL supports a pattern known as change data capture.

All data is immediately written to a persistent log on the filesystem without necessarily flushing to disk. In effect this just means that it is transferred into the kernel’s pagecache.

Competitors like redpanda ship raft while warpstream does interesting things with distributed mmap and stateless agents, a different can of worms.

The challenge is thankfully much simpler – than having to implement distributed mmap or pulling in something like zookeeper or raft, we have yet again a magical convenient linearizable key value store, damn that’s a nice primitive to have lying around. Why?

node := maelstrom.NewNode()

kv := maelstrom.NewLinKV(node)

A lin-kv is ideally all you need, wheter it’s powered by raft or the sun god Ra, we’ve solved the difficult distributed systems problems of ordering and agreement across replicas when the leader dies, in the face of network partitions or concurrent servers which accept writes – one source of truth.

Kafka dynamically maintains a set of in-sync replicas (ISR) that are caught-up to the leader. Only members of this set are eligible for election as leader. A write to a Kafka partition is not considered committed until all in-sync replicas have received the write

In this much more simplistic model:

type replicatedLog struct {

committed map[string]float64

version map[string][]int

log []entry

global sync.RWMutex

}

type entry struct {

key string

value float64

offset float64

}

- a producer needs to send an “event” or message to be appended, this is an active replication of the state machine:

Using FIFO-total order broadcast it is easy to build a replicated system: we broadcast every update request to the replicas, which update their state based on each message as it is delivered. This is called state machine replication (SMR)

when using state machine replication, a replica that wants to update its state cannot do so immediately, but it has to go through the broadcast process, coordinate with other nodes, and wait for the update to be delivered back to itself.

// MUST BE: Linearizable

func (s *session) sendHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

var body map[string]any

var retries chan retry

var wg sync.WaitGroup

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

// reserve a monotonic count slot

offset := s.log.acquireLease(s.kv)

for _, dest := range s.node.NodeIDs() {

wg.Add(1)

go func(dest string) {

deadline := time.Now().Add(400 * time.Millisecond)

ctx, cancel := context.WithDeadline(context.Background(), deadline)

replicaBody := map[string]any{

"type": "replicate", "offset": offset,

"key": body["key"], "msg": body["msg"],

}

defer cancel()

defer wg.Done()

_, err := s.node.SyncRPC(ctx, dest, replicaBody)

if err == nil {

return

} else {

retries <- retry{body: replicaBody, dest: dest, attempt: 20, err: err}

}

}(dest)

}

wg.Wait()

go rebroadcast(s, retries)

// we must ensure this write broadcast is atomic and replicated to a quorum

// for real kafka this is the ISR quorum, for me, this is 2/2 eazy peazy

if len(retries) > 0 {

panic("non-atomic broadcast")

}

return s.node.Reply(msg, map[string]any{"type": "send_ok", "offset": offset})

}

- a consumer can ask or poll for new events:

func (l *replicatedLog) Read(offsets map[string]any) map[string][][]float64 {

l.global.Lock()

defer l.global.Unlock()

var result = make(map[string][][]float64)

for key, offset := range offsets {

// we can binary search the log!

// or partition and route our search

// and do all sorts of fun caching :)

result[key] = l.seek(key, int(offset.(float64)))

}

return result

}

- a client can synchronise processed offsets with the server(s):

func (l *replicatedLog) Commit(kv *maelstrom.KV, offsets map[string]any) {

l.global.Lock()

defer l.global.Unlock()

for key, offset := range offsets {

l.committed[key] = offset.(float64)

}

}

- a client can read from the latest committed offset:

func (l *replicatedLog) ListCommitted(keys []any) map[string]any {

l.global.RLock()

defer l.global.RUnlock()

var offsets = make(map[string]any)

for _, key := range keys {

key := key.(string)

offsets[key] = l.committed[key]

}

return offsets

}

Because this is a toy, the log grows forever, that’s not okay – compaction is it’s own can of worms. The log is also not persisted, which it would have to be in a real implementation as these datasets are typically large record batches that do zero-copy from network to disk, it’s also inefficient, ideally we’d want to actually partition the log for availability. However I’m satisfied with the overall solution.

:availability {:valid? true, :ok-fraction 0.99947566},

:net {:all {:send-count 91240,

:recv-count 91240,

:msg-count 91240,

:msgs-per-op 5.980206},

:clients {:send-count 37488,

:recv-count 37488,

:msg-count 37488},

:servers {:send-count 53752,

:recv-count 53752,

:msg-count 53752,

:msgs-per-op 3.5231042},

:valid? true},

:workload {:valid? true,

:worst-realtime-lag {:time 0.261327208,

:process 4,

:key "9",

:lag 0.0},

:bad-error-types (),

:error-types (),

:info-txn-causes ()},

:valid? true}

All anyone has to do to build on this knowledge and make actual real life kafka is build literally everything else for the rest of your life.

6. Totally-Available Transactions

Finally, a distributed key-value store with transactions, or rather something simpler resembling the real thing. I promised we would revist transactions, why and how kafka offers these semantics and demystifying transactions in general, here we are!

Transactions are a deep topic but first ACID, we’re interested in specifically the ‘C’ in there first - consistency. Before a bunch of theory what’s our goal here?

- weak consistency (here be dragons!)

- total availability (in CAP terms - AP)

We’ll revisit why these semantics matter. Let’s focus on understanding the requirements as we go,

we need to define a handler that takes a single message/data structure with list of operations that look like:

[["r", 1, null], ["w", 1, 6], ["w", 2, 9]].

which means our handler needs to:

- read from kv[1]

- write to kv[1]=6

- write to kv[2]=9

we can re-use the store from earlier as a key-value store:

type store struct {

index map[int]int

log []float64

}

all there is to figure out is the parsing for the above semantics:

txn := body["txn"].([]any)

var result = make([][]any, 0)

for _, op := range txn {

op := op.([]any)

if op[0] == "r" {

index := op[1].(float64)

result = append(result, []any{"r", index, kv.log[int(index)]})

} else if op[0] == "w" {

index := op[1].(float64)

value := op[2].(float64)

kv.log[int(index)] = value

result = append(result, []any{"w", index, kv.log[int(index)]})

}

}

we try out empirically our first consistency model read uncommitted, huh – that was easy? what’s all the fuss about these SQL anomalies and stuff? dirty writes? phantom skews? 20

Read uncommitted is a consistency model which prohibits dirty writes, where two transactions modify the same object concurrently before committing. In the ANSI SQL specification, read uncommitted is presumed to be the default

but of course there’s no free lunch, not really.

The ANSI SQL 1999 spec places essentially no constraints on the behavior of read uncommitted. Any and all weird behavior is fair game.

All we need to do to prevent dirty writes is a sync.RWMutex:

kv.global.Lock()

defer kv.global.Unlock()

There are “bugs” here, just depends on what the agreed upon definition is 21 – what it boils down to, is what isolation and consistency models are really about. What are the semantics and rules can we agree on what is desired behaviour? is it fast? We’ll get to that, next we need to replicate these transactions to every other node – all we have to prevent for now is the write-write conflict.

Read uncommitted can be totally available: in the presence of network partitions, every node can make progress.

Friendly reminder in CAP terms, this is AP - not consistent.

Moreover, read uncommitted does not require a per-process order between transactions. A process can observe a write, then fail to observe that same write in a subsequent transaction. In fact, a process can fail to observe its own prior writes, if those writes occurred in different transactions.

interesting isn’t it? Which is to say without replicating the data how would you really know the difference?

go install . && ../maelstrom/maelstrom test -w txn-rw-register \

--bin ~/go/bin/maelstrom-txn --node-count 2 --concurrency 2n \

--time-limit 20 --rate 1000 --consistency-models read-uncommitted \

--availability total --nemesis partition

lulls us into a false sense of security:

Everything looks good! ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

but let’s follow the requirements maybe this is going somewhere, we replicate it over the FIFO broadcast protocol from earlier, but don’t gossip:

func (s *session) replicateHandler(msg maelstrom.Message) error {

var body map[string]any

if err := json.Unmarshal(msg.Body, &body); err != nil {

return err

}

s.kv.Commit(body["txn"].([]any))

return s.node.Reply(msg, map[string]any{"type": "replicate_ok"})

}

:net {:all {:send-count 53194,

:recv-count 53072,

:msg-count 53194,

:msgs-per-op 4.009497},

:clients {:send-count 26538,

:recv-count 26538,

:msg-count 26538},

:servers {:send-count 26656,

:recv-count 26534,

:msg-count 26656,

:msgs-per-op 2.0091958},

:valid? true},

:workload {:valid? true, :anomaly-types (), :anomalies nil},

:valid? true}

Everything looks good! ヽ(‘ー`)ノ

Lastly, a stronger, somewhat more useful guarantee read-committed, read committed prevents a new class of anomalies: dirty reads.

:workload {:valid? false,

:anomaly-types (:G1b),

:anomalies {:G1b ({:op #jepsen.history.Op{:index 18240,

Thankfully there’s a hint about the anomalies checked:

G1a (aborted read): An aborted transaction T1 writes key x, and a committed transaction T2 reads that write to x.

G1b (intermediate read): A committed transaction T2 reads a value of key x that was generated by transaction T1 other than T1’s final write of x.

G1c (circular information flow): A cycle of transactions linked by either write-read or read-write dependencies. For instance, transaction T1 writes x = 1 and reads y = 2, and transaction T2 writes y = 2 and reads x = 1

In essence this means we must handle when transaction conflicts occur, specifically

we introduce/discover the concept of a commit.

when do we offer commit comes down to what rules determine wheter a transaction aborts, and these give birth

to what we know as isolation levels.

This is a pernicious problem because isolation levels are often weakened to enable better concurrency/performance.

Throwing a Mutex on it and ensuring the data we replicate is what we commit else aborting is a simple solution that does work but it’s boring. These are classifications that come up in multiversion concurrency/optimistic concurrency control and are relaxed constraints on ordering enable eeking out performance, you just can’t get with a pessimistic lock, but this article is long enough :)

if len(s.retries) > 0 {

return s.node.Reply(

msg,

map[string]any{

"type": "error",

"code": maelstrom.TxnConflict,

"text": "txn abort",

},

)

}

:workload {:valid? true,

:anomaly-types (),

:anomalies {},

:not #{:cursor-stability :read-atomic},

:also-not #{:ROLA

:causal-cerone

:consistent-view

:forward-consistent-view

:parallel-snapshot-isolation

:prefix

:repeatable-read

:serializable

:snapshot-isolation

:strong-serializable

:strong-session-serializable

:strong-session-snapshot-isolation

:strong-snapshot-isolation

:update-serializable}},

:valid? true}

7. Testing, Model Checkers and Simulators

If you’ve been wondering, since these are just toy models, what’s the delta between these simplified ideas and the real world? They are obviously not intended for production and maelstrom is a teaching tool.

Where are the “unit tests”? If maelstrom/jepsen says so, does it make these implementations correct? maybe.

Intuitively, if you’ve gotten this far, you should feel in your bones, distributed systems are different from single node ones. The way we test them must change, because they require a fundamental shift in thinking to reason about and therefore verifying correctness of primitives. This is a hard problem with no easy answers. An overview of interesting things to explore in the space:

- TLA+

- Hermitage

- Deterministic simulation testing: ala foundationdb, tigerbeetle’s vopr, antithesis and much more I probably haven’t discovered.

If that sounds like a pretty high bar for correctness it’s because it is. Verifying the correctness of distributed systems/databases is a non-trivial problem, when building applications implictly there’s trust that the claimed semantics are true, composing them properly is a different matter entirely. Maelstrom uses jepsen/elle22 the model checker which powers a fair bit of some the invariant checks, which is way over my head at this time.

An ideal checker would be sound (no false positives), efficient (polynomial in history length and concurrency), effective (finding violations in real databases), general (analyzing many patterns of transactions), and informative (justifying the presence of an anomaly with understandable counterexamples). Sadly, we are aware of no checkers that satisfy these goals.

Sounds a lot more rigorous than a unit test no?

and that’s it! fun with distributed systems, scalability but at what COST?, here’s LMAX doing 100k TPS in < 1ms in 2010 on a single thread of “commodity hardware”, distributed systems are a necessary evil requiring a different lens.

References

https://datatracker.ietf.org/doc/html/rfc4122#section-4.2.1 ↩︎

https://www.cockroachlabs.com/blog/living-without-atomic-clocks/ ↩︎

https://docs.riak.com/riak/kv/2.2.3/learn/concepts/clusters.1.html ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.cs.cornell.edu/projects/Quicksilver/public_pdfs/SWIM.pdf ↩︎

https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~rossbach/cs380p/papers/Counters.html ↩︎

https://www.rabbitmq.com/docs/confirms#acknowledgement-modes ↩︎

https://mesos.apache.org/documentation/latest/replicated-log-internals/ ↩︎

https://blog.x.com/engineering/en_us/topics/infrastructure/2015/building-distributedlog-twitter-s-high-performance-replicated-log-servic ↩︎

https://engineering.linkedin.com/distributed-systems/log-what-every-software-engineer-should-know-about-real-time-datas-unifying ↩︎ ↩︎

https://www.cs.cornell.edu/fbs/publications/ibmFault.sm.pdf ↩︎

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2008/02/tr-2008-25.pdf ↩︎

https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/tr-95-51.pdf ↩︎